CUHK

News Centre

CUHK palaeontologist identifies earliest evidence of macrocarnivory in birds

An international palaeontological research team led by The Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) has identified the earliest evidence of a bird being a macrocarnivore, an animal that hunts and kills large animals. As part of their investigation into the diet of ancient birds, the team set out to investigate a 130-to-120-million-year-old family of birds known as Pengornithidae. They identified traits of Pengornis including large body size, moderately strong jaws, and enlarged and highly curved claws, which have converged with living raptorial birds, pushing back their origin by at least 35 million years. The team’s work has brought with it revelations about the origin of flight and a deeper understanding of how ecosystems functioned before a meteor wiped out non-avian dinosaurs. Their findings were published in the international interdisciplinary journal iScience.

The mystery of Pengornithidae’s main food

Pengornithidae is one of the best-known families of fossil birds. “They have a fascinating mix of characteristics,” said Dr Michael Pittman, Assistant Professor from CUHK’s School of Life Sciences. “Their skulls are very similar to the earliest birds like Archaeopteryx, and even to some dromaeosaurids like Velociraptor, but their wings are more similar to living birds than they are to the wings of many of their close relatives.” Larger than most other birds at the time, and with many more teeth, pengornithids stand out in the fossil record. Their numerous small, low teeth have led past researchers to propose that they were minimally carnivorous, while others have suggested they were specialised for eating invertebrates, but disagreed on whether these were mainly soft-bodied or hard-bodied. These contradictory hypotheses spurred Dr Pittman and his team to test them with quantitative data.

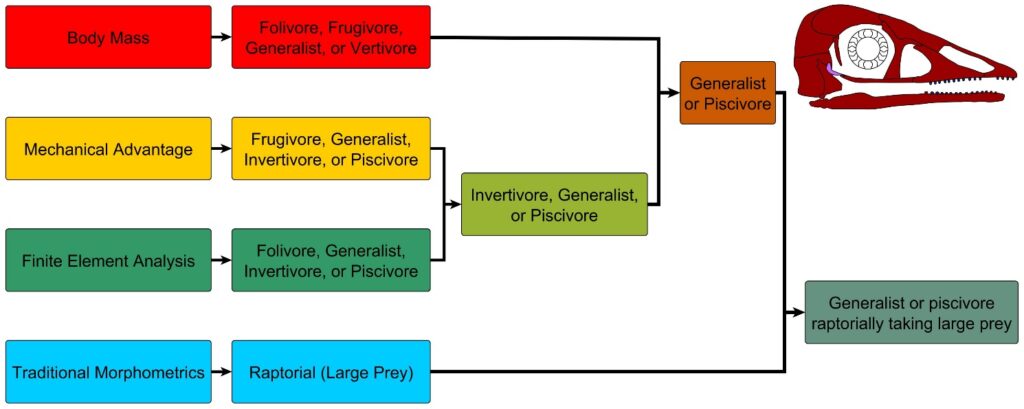

The team found most pengornithids were most likely to prey on fish. They are larger than most invertebrate-eating birds and have weaker jaws than most plant-eating birds. Pengornis, though, differs from other pengornithids. It has large, highly curved claws like a hawk or eagle, as well as a bird-like jaw for eating a wide variety of foods. “It didn’t make sense at first,” said Case Vincent Miller, the first author of the research and Dr Pittman’s PhD student at The University of Hong Kong. “Why would a bird have claws clearly meant for killing animals, but a jaw and teeth that seem equally useful for eating plants? Through our research, we learned about a living bird called the crested caracara. They eat anything: they use their claws to take down animals several times their size, but also forage for fruits, insects, carrion and more. The area Pengornis lived in had a huge variety of potential food sources, and it seems like this bird evolved to take advantage of many of them.”

Study shows the evolutionary history of bird diet and flight was complex

Killing and eating large prey is not well-documented in the history of birds. One 85-million-year-old family from North America, Avisauridae, has been proposed as a raptorial family based on fragmentary remains. Aside from them, birds were not previously thought to hunt large prey until the evolution of storks and eagles about 65 million years ago. “Before this study, I would have said the niches of modern predatory birds were filled by dromaeosaurids during the Mesozoic,” said Dr Pittman. His recent research revealed that at least one dromaeosaurid from the same area as Pengornis did hunt like a raptorial bird, so some overlap must have occurred.

These dietary trends also have interesting implications for the evolution of flight. Multiple recent studies have suggested that at major transitions in bird evolution, birds evolved adaptations for stronger flight at the same time that they began to eat animals or plants lower on the food chain. Pengornithidae, though, included some of the strongest fliers among early birds while also being relatively high on the food chain. The team does not think their findings contradict this larger trend, pointing out that there may have been countless lineages of birds that developed advanced flight abilities but died out before the non-avian dinosaur extinction.

“I am excited to see where this new information takes us. Flight unlocks so many new ecological niches, and the more we study early birds and bird-like dinosaurs, the more diversity we find,” said Dr Pittman.

Miller added, “I look forward to studying how this refines our reconstructions of Mesozoic ecosystems more broadly. Early birds are usually all assumed to occupy lower levels of the food chain by default, but our new findings suggest there were many more intricate and complex interactions going on than we previously thought.”

The international research team includes Professor Wang Xiaoli from Linyi University, Professor Zheng Xiaoting from the Shandong Tianyu Museum of Nature, and Dr Jen A. Bright from the University of Hull.

Full research paper can be found at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2589004223002882

Reconstruction of the early fossil bird Pengornis feeding on a large osteoglossomorph fish (Lycoptera davidi) and fruits of a thuja tree. Lycoptera is related to the living Asian arowana or “dragonfish”. Thujas are a group of cypress trees common in the northern hemisphere and beloved by many groups of living birds. Miller et al. describe Pengornis as adapted for eating a variety of foods such as fish and fruit. Image credit: Julius T. Csotonyi.