Professor Annett Schirmer – Using Nonverbal Behaviours as Tools of Influence

Professor Annett Schirmer – Using Nonverbal Behaviours as Tools of Influence

Traditionally, nonverbal behaviours have been understood as body language. A sender was thought to communicate with a receiver via a nonverbal code. However, based on her work, Professor Annett Schirmer of CUHK Department of Psychology doubts that this is all there is to nonverbal behaviours. Indeed, she speculates that these behaviours may have another primary function which is to benefit the individual through self-regulatory and socially mediated effects. “When we’re nonverbal, we’re actually using behaviours as tools of influence on ourselves and on other people.” Professor Schirmer’s excellent research achievements gained her the 2019 Humanities and Social Sciences Prestigious Fellowship from the Research Grants Council (RGC). Her research findings are significant in addressing important social mechanisms and potential problems resulting from societal change as in the context of COVID.

“We don’t smile just to say we’re happy”

Charles Darwin, one of the first scientists studying nonverbal behaviours, published a book entitled The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals in 1872. In this book, he raised the idea that some nonverbal behaviours emerged because they served a particular purpose. Professor Schirmer explained, ‘For instance, we are not wrinkling our nose to communicate to someone that we are disgusted. Instead, this “expression” reduces nasal airflow and the amount of offending odor we are breathing in. We open our eyes wide when we are afraid not because we wish to share our fear with others. Instead, this facial change improves our vision.’

Professor Schirmer’s primary interest lies with social touch and the way we are using physical contact in interpersonal interactions. Such touch serves a range of short and long-term functions. In the short-term, it can induce pleasure and reduce stress. In the long-term, it can shape social processing circuits in our brain. Professor Schirmer’s previous research shows that the amount of touch children receive from their parent predicts how likely they are to orient towards social information in their environment and how good they are at recognizing emotions. Touch frequency also predicts the brain’s functional connectivity in networks that support our ability to put us in another person’s shoes. Notably, these findings parallel work in non-human animals that has uncovered underlying epigenetic mechanisms – that is mechanisms by which touch influences the expression of genes in the brain.

Professor Schirmer discussed the above findings with a smile on her face and in a positive tone of voice. She may not have done it purposefully, but these nonverbal clues can make others feel that what she is working on is interesting and fun.

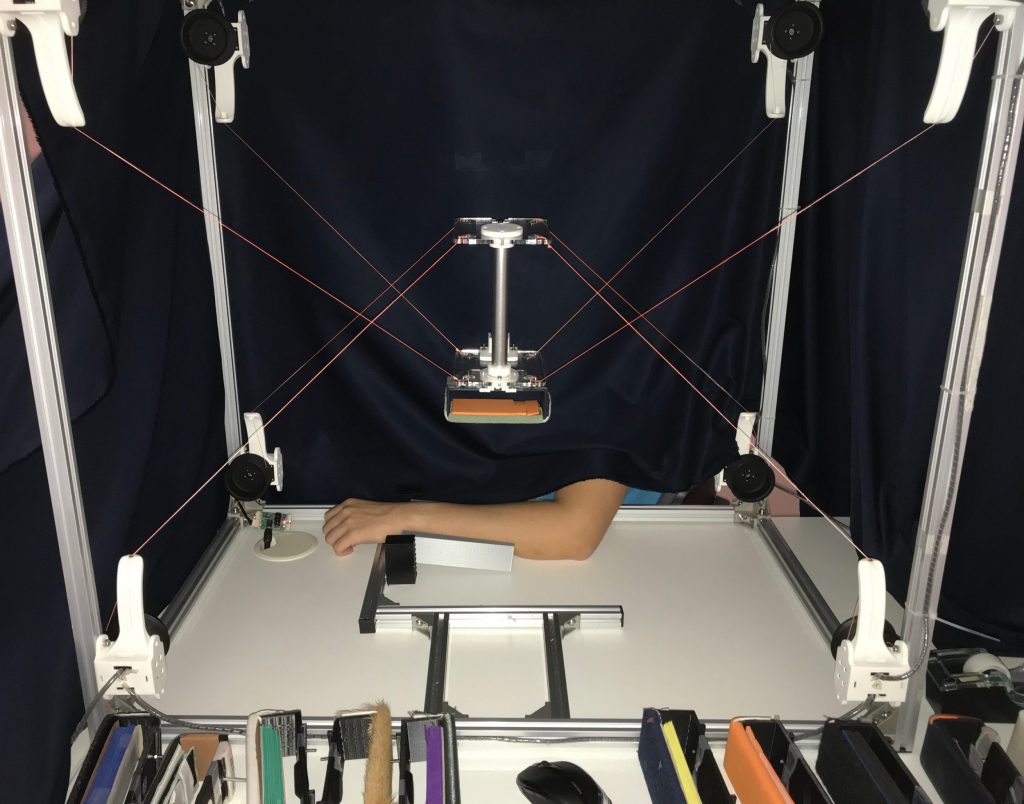

There are different stroking setups for a research about touch. In this experiment, participants’ hand motion is being recorded with a motion sensor helping to decipher how we touch.

Psychologists are Scientists. How to measure nonverbal behaviours and perceptions?

“I was always interested in the brain.” Starting off her research life at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Germany, Professor Schirmer has been investigating the brain basis of nonverbal processes with an emphasis on the voice and touch for more than twenty years. “The nice thing about working in an area for a longer period of time is that everything just becomes easier with time, fitting me like a glove now.” In 2020, she was listed among the world’s top 2% scientists by Stanford University.

Conventional wisdom feels and fancies, but a psychologist experiments and examines. Professor Schirmer laughed at herself and said she was bad at reading the emotions from other people. Instead, she is an expert at quantifying and measuring biological processes. She quantifies touch by considering its velocity, pressure and temperature, and measures brain processes by using electroencephalogram (EEG) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). She might also track eye gaze and heart rate to look at stress responses.

Her novel project to explore the different tactile pathways

Many labs, including that of Professor Schirmer, focus on the study of a special tactile receptor called the C-tactile afferent or CT for short. CTs are most densely represented in hairy skin, and absent from the glabrous skin that we find on our palms. CTs are interesting because they will fire most vigorously when stimulated with a touch of low pressure, slow velocity and skin temperature. “We may be able to explain most positive effects of touch by understanding CTs.”

By presenting participants with different surface textures, Professor Schirmer’s team identified the somatosensory characteristics that maximize tactile pleasure. She also showed that touch we perceive as most pleasurable is touch that feels most human.

Professor Schirmer’s award-winning project “A new gating theory on the convergence of ‘discriminative’ and ‘affective’ touch” goes beyond just one type of receptor fibre, “We believe there are interactions between CTs and other types of mechanoreceptors, such as Aβ fibres.” CTs project very slowly taking about 700 milliseconds to reach the brain from the arm. When CT signals arrive in the brain, the Aβ signal is already there as it arrives in only a few milliseconds after the touch input. “The Aβ signal could be a gatekeeper to up- or down-regulate the CT input, so that we respond to CT input in an optimal way.” The novel theory that Professor Schirmer is developing integrates the two signals to explain the emergence of positive feelings from touch and enables the exploration of the different tactile pathways.

Supplementing the missing interpersonal touch under COVID

Understanding the tactile system can help with developing applications that supplement reduced or missing tactile input. “Many of us are missing touch, especially now during COVID when we practice social distancing.” Professor Schirmer is collaborating with researchers from the Department of Mechanical and Automation Engineering to develop smart materials like a wearable that people can put on and which optimally stimulates CT fibers. “That would be really cool,” she said. It would not only help people in a pandemic, but could also support medical care in individuals confined to ICUs or isolated elderly, and might facilitate socio-emotional processes in individuals with clinical disorders such as autism or those serving a prison sentence.

Taking pleasure from everything, including teaching

Other than doing research, Professor Schirmer is also passionate about teaching. “I have learned so much in my career that I have an obligation to pass that on.” In her fourth year at CUHK, she has been teaching a range of courses from small graduate seminars to core modules with 130 or more students. She does her research primarily in the evening and on weekends during a teaching semester. Having such a tight schedule, she manages to take pleasure in the things that she does. She finds it very rewarding when students who hated biological psychology in the beginning learn why it is cool and exciting in the end. “No matter what you do, there will always be aspects that can be very engaging and exciting. As long as you find and enjoy those, you will be successful. This is my motto.”

Not only do nonverbal behaviours influence people, but Professor Schirmer’s enthusiasm for research and teaching does as well.

Professor Schirmer (second right) loves the countryside of Hong Kong. She sometimes hikes with her lab team.

Professor Annett Schirmer is an expert in nonverbal behaviours. Professor Schirmer’s primary interest lies with social touch and the way we are using physical contact in interpersonal interactions. Her life motto is "“No matter what you do, there will always be aspects that can be very engaging and exciting. As long as you find and enjoy those, you will be successful.”